So this is it, the end of Informing Contexts and the beginning of the final stage of this Masters degree. I can’t believe how quickly we’ve arrived here. I’ve learnt loads, with many of the lessons still being absorbed as I try to understand how to relate the learning to my own practice. I approach the Final Major Project (FMP) with some nervousness, mainly just because I’m not sure what the format of the next few months will be, but I’m also excited by the prospect of hopefully being able to put everything together into a cohesive vision of this project.

A frustration of mine has been that the 12-week module rhythm, with the need to prepare for summative assessments at the end of each one, hasn’t always correlated with the speed at which I’m able to absorb and respond to the lessons I’ve been learning along the way. Often I’ve found myself having the biggest revelations and making the largest steps between the modules, as the absence of course demands gives me the time to reflect, let things sink in and embed into my thought process about what I want to do. Due to the demands of my job, I often feel like I’m just hanging on for dear life during the modules trying to keep up, rather than having space and time to truly assimilate the information and allow my practice to develop. This has been a particular problem during this module as I approach the end of my medical training and so have had the most important exams of my career to prepare for, alongside working and doing this MA. Those demands, as well as my struggle to see a way to move forward with the photography (‘the narrative conundrum’ I think I’m now going to call it!) has meant this has been the module I’ve found most difficult so far.

As previously, I’m confident that the period immediately after assignment submission (which again coincides with another big work thing) will be a productive one, both in terms of the images I’ll be making as well as in terms of putting a clear plan in place to attack the FMP. It arrives too late to be absolutely reflected in the WIP for this module but, as I’ve written elsewhere, I have a much better sense of the images I want to make and how to hopefully create interesting photographs. I will also be bringing people (and possibly also myself) into the work in some way and have only just been able to start experimenting with this.

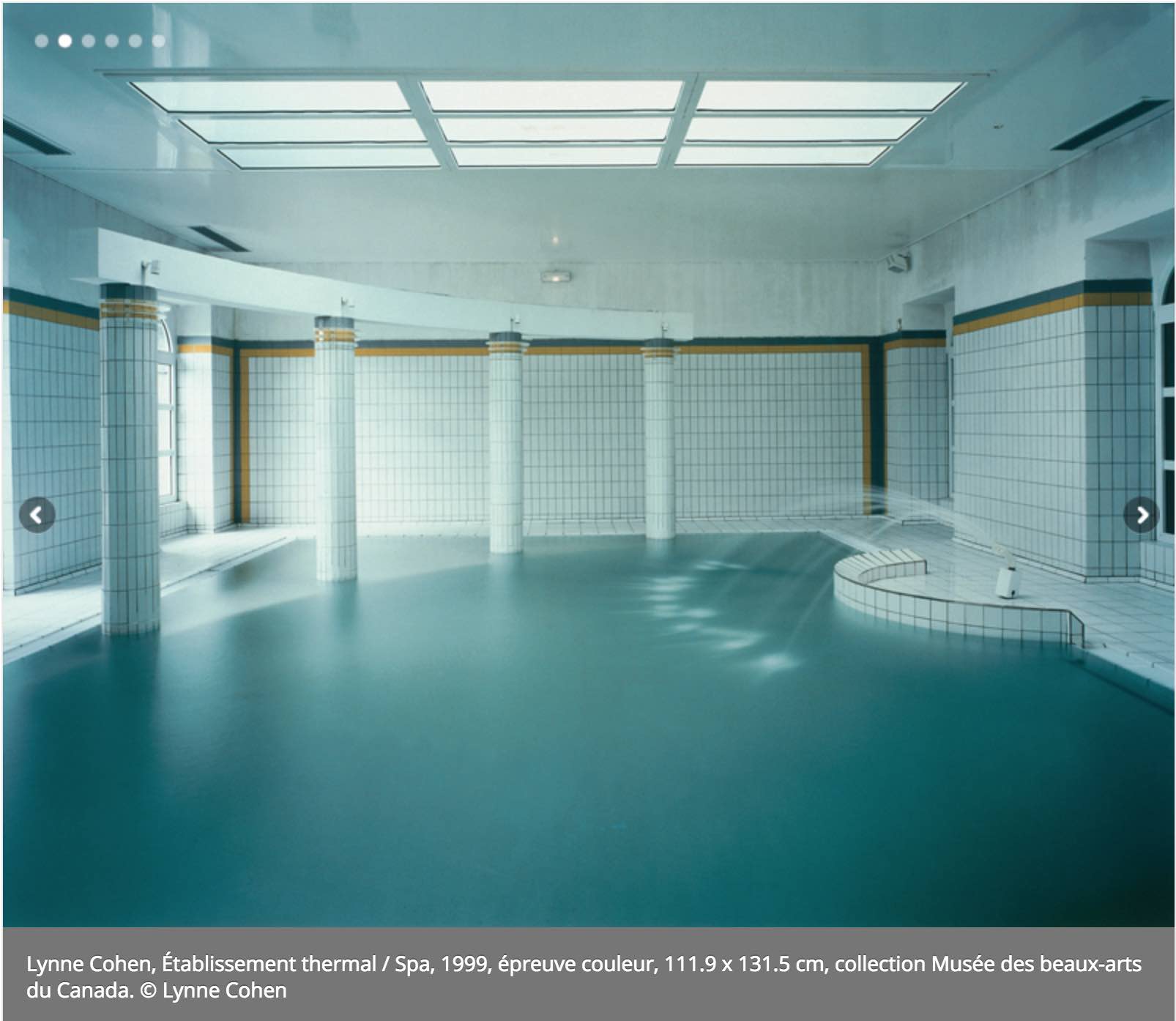

Something else that I’m looking forward to exploring further is the internal environment and how this relates to our experiences of solitude. My work has almost exclusively focused on outdoor urban spaces to this point, but reflecting on how people experience solitude and isolation in many hidden or public indoor places (bedrooms, cars, pubs etc.) and inspired by the work of practitioners such as Lynne Cohen and Andrew Emond I am really keen to explore interior spaces and make this an important part of the work moving forward. This actually now feels like a big omission from the project to date, an oversight on my part, and I envisage interiors becoming increasingly integral to telling the story of urban solitude in my FMP.

The work of Andrew Emond, from his Objects of Consequence series

Despite the misgivings I stated above I do feel I’ve made progress during this module. I’ve continued to write, with more book reviews published and in progress.

My most recent book review on Shutter Hub

I’m aiming to continue developing this area of my practice. I’m still trying to find a short writing course that I think will help me to develop my writing style and that is feasible for me to do over the next few months alongside all my other commitments. The ones I’ve been interested in so far are either too involved (essentially a writing MA) or too inconsequential to be worthwhile. I’m increasingly of the view that text will be a substantial part of the final work, and though this is not likely to be all my own writing, I do feel I’d benefit from having more competence and confidence in this area. Using practitioners such as David Campany and Lewis Bush as inspiration, I hope to make this a solid strand of my practice moving forward.

I was happy to be selected as a ‘shortlisted artist’ for the Revolv Collective One Year Open Call which will involve some much welcome social media promotion via their channels and may open further opportunities in the future. I have also entered work into the Royal Photographic Society’s International Photography Exhibition 161, with the outcome of shortlisting currently awaited.

I’m looking forward to what I anticipate will be the most intensely rewarding period of the MA to come in the Final Major Project. I feel that my work is on the verge of blossoming into something different and hopefully more compelling. I’m excited about the possibilities ahead and have already begun to consider the future beyond the MA, where I know the work will continue (PhD?). I’m relishing the opportunity to spend more focused time researching, exploring and developing new ideas and creating new connections with the work I have planned (workshops, joint projects with key agencies already involved with issues surrounding loneliness and urban isolation etc.).

I look forward to discovering where the work will evolve to and how it will broaden out to hopefully include people (of all ages), interiors, exteriors and maybe even some daylight! I am less daunted by the FMP simply because I understand now that my work on this issue will not stop there, and I have a sense of where I will be able to take this work forward in the post-MA world that will soon be a reality.

Let’s get it!