This week we’ve been looking at how viewers interpret images and whether the intent of the photographer can ever result in a ‘dominant’ reading. We were presented with a range of images, many from advertising campaigns, and challenged to consider how a shared understanding of visual and cultural references might influence their interpretation.

To use a couple of examples here:

The Falling Man by Richard Drew

This photograph immediately evokes my own memories of where I was on September 11th 2001 when these terrible events began to unfold. These events are now so deeply embedded in our collective consciousness that seeing an image like this causes so many thoughts to surge forward - ‘The war on terror’, America, New York, George Bush, Tony Blair, Iraq, Saddam Hussein, Osama Bin Laden, missing persons, the sense of a world before and after this moment – to name just the first few that spring to mind. I imagine that most people reading this would understand instantly how this image fits into the wider social, cultural and historical landscape and would need no further explanation of the events that it connotes.

Marilyn Monroe by Sam Shaw

To me this photograph conjures glamour, sex symbol, JFK, Hollywood, cinema, 1950s. The fame of Monroe, who remains a revered icon many years after her death, allows for a shared understanding of her significance and to be presented with an image of her is likely to result in a number of shared associations.

So, does the way an image communicates rely entirely on shared references? Must the viewer and the photographer have a shared cultural and visual lexicon for the image to connect? I’m not sure where I stand on this question. Instinctively, I feel like shared references significantly improve the chances of an image being received in the way it was intended. In advertising for example, controlling the likely message your visual information communicates is key. Whether this can ever be controlled absolutely doesn’t remove the imperative of trying to shape the narrative as much as possible.

I also feel like any successful photograph probably succeeds by somehow tapping into a universal sentiment that allows the viewer to relate to the image before them and find something in it to which they can apply a personal relevance, even if only on a subconscious level. Conversely, I also think that it’s possible to make an interesting or ‘good’ photograph without any conscious attention to any of these things. I’m unable to reconcile these two opposing ideas into a coherent conclusion as yet. I think this question relates back to my ongoing struggles with understanding ‘narrative’ and how I might bring this understanding into hopefully improving my own work.

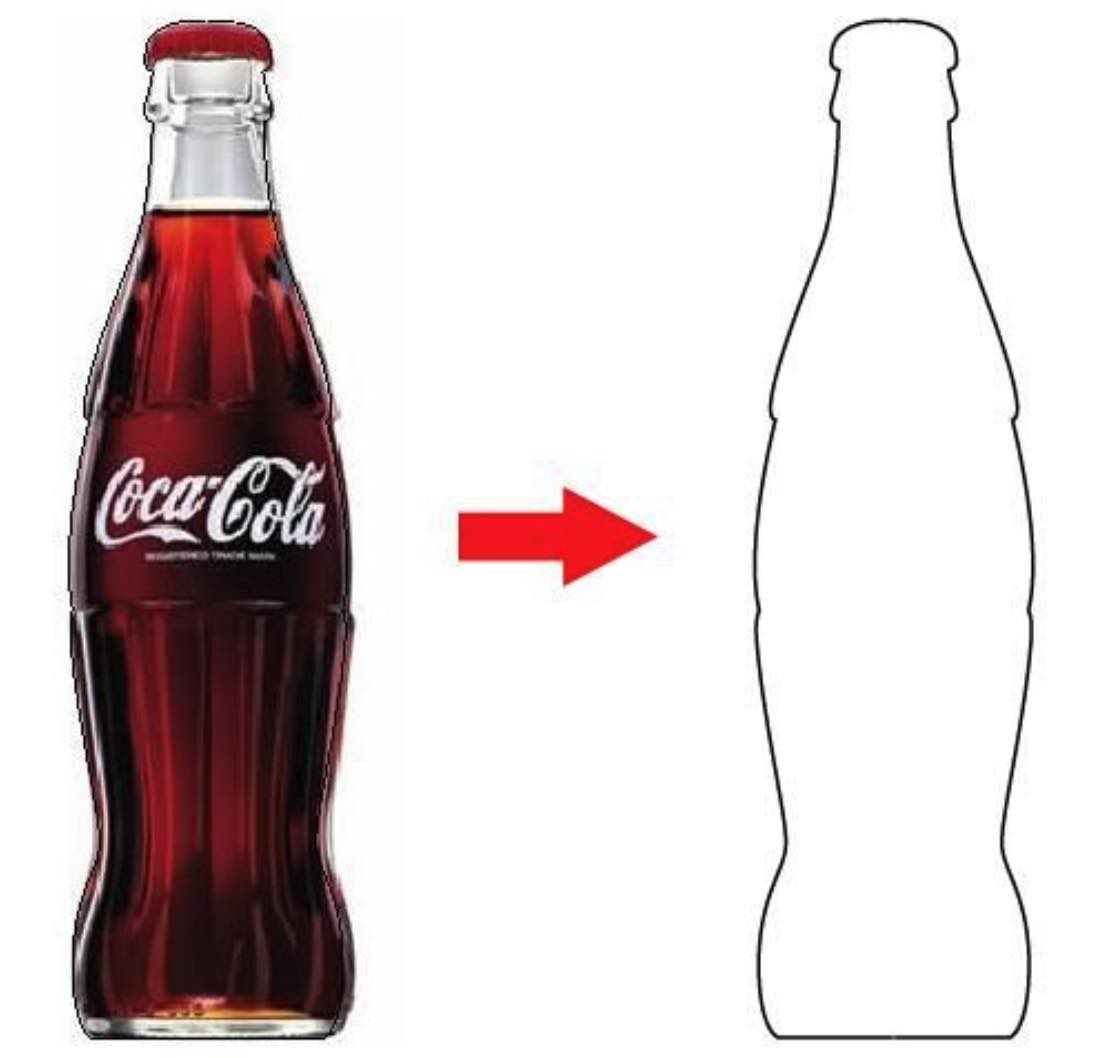

No words are required to understand what this is

Another question raised this week is how text can relate to images and help to mediate meaning. I certainly think it’s possible to communicate with a photograph, without the aid of supporting text. I do however also believe that text can be used to anchor a concept that can then be further explored visually in an image or series of images.

Again using advertising as an example, text can help to establish the narrative of a brand or product, particularly if that product is new to the marketplace. In such cases, it may well be possible to dispense with text once the product and its supposed characteristics have been established and accepted (e.g. Coca Cola) but text may be important in the early stages of a product’s life to guide the customer in the desired direction.

In all of this it’s important to consider, if not also try to influence, the relationship between images and viewer. This possibly begins with the intent of the work, and aiming to produce work that is considered, well-researched and grounded in a personal truth (whatever that might mean). The relationship between image and viewer strikes me as a mysterious and possibly unknowable one. I don’t suppose we can ever truly know what the viewer will see when they look at our work. There’s a certain arrogance in expecting the viewer to see it in the same way you do, or believing that your interpretation is the only possible reading. There’s no way to account for the viewer’s personal history, their sense of humour, their cultural references, their mood at the time – all factors that might influence the way the viewer receives and interprets the image before them.

There’s also something to be said for creating open-ended narratives, allowing space for the viewer to create their own stories, using your work as the starting point. This potentially offers the work to a broader audience, if in some way you can be all things to all people, simply reflecting the viewers back to themselves in a way that is neither too confronting or banal. So ambiguity of meaning can be a valid approach, and also possibly acknowledges the fact that you can never entirely control the meaning of the work anyway.

The skilled practitioner will be comfortable with this, while being careful to use commonly accepted signifiers as far as possible if the intention is to speak clearly in the work. Whether the use of commonly accepted signifiers results in a limited palette from which to paint and whether that then results in work lacking in expressivity or individuality is something to be considered. These are questions we all must answer for ourselves: what is the intent and how far are we willing to go to try and influence this mystical space between the image and the viewer’s perception?

Increasingly in my own work I’m trying to edge closer to a representation of an internal state that feels uncomfortable, vulnerable, but also somehow mundane and entirely normal. Previously, my strategy has been quite literal, very visual and not very subtle or varied. This approach now seems quite redundant and so I’m scratching around, trying to find a more nuanced way to communicate, a way to do visually what I have not yet managed to do verbally. That’s why it’s so hard I guess. But I’ll keep working at it.