To those of us who spend possibly more time than we should contemplating the way the world is, and not quite enough time simply diving feet first in to the ever-changing quotidian tide of life, the last couple of years have thrown up a number of additional points for consideration. Towards the end of last year I wrote a piece for a forthcoming publication based on a topic I’d been thinking a lot about since the beginning of the pandemic. I re-read that piece again this week and felt I’d done a less than superb job of articulating what my concern actually was and so, dear patient reader, I’ve chosen to inflict my second attempt to explain myself on you :)

In the early phase of the pandemic I was struck by how quickly we all became totally dependent on technology to mediate our connections with each other. These technologies were already available and in regular use of course but as events forced us indoors, often alone, we all had no choice but to download Zoom and adapt. Former technophobes were unmuting and hopping in and out of breakout rooms with masterful ease and it seemed that, on the face of it, the circumstances were at least encouraging more people into a more connected online life that would ultimately be enriching for them personally, as well as ushering in new ways of working and methods of relating to one another for all of us.

At this point many will agree that this has indeed been the outcome, will happily chalk it up as yet another success for the modern world and move on to more pressing concerns. To those folk, thanks for popping in…

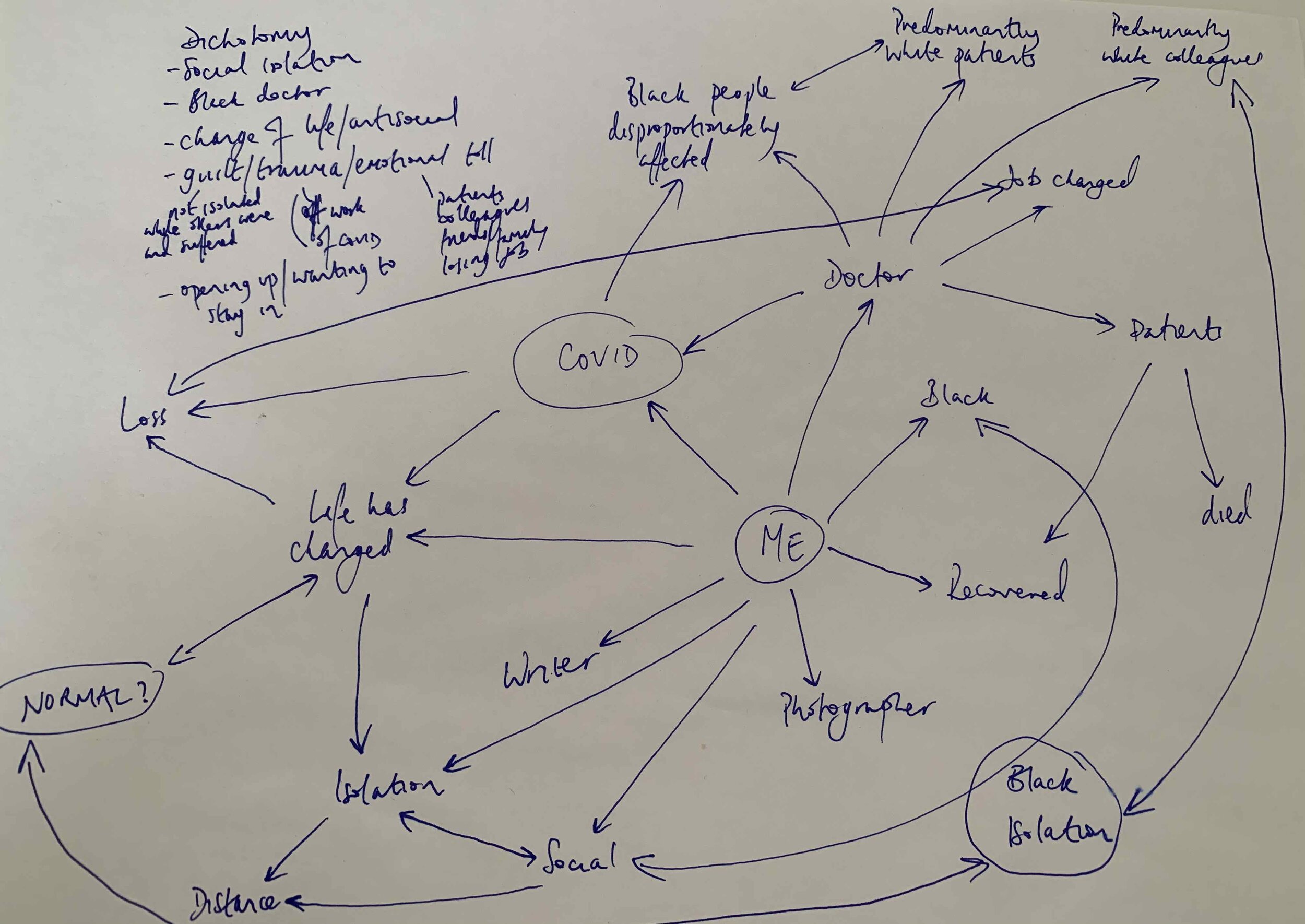

An image from the Reaching Out Into The Dark project

I’ve long been interested in the way people experience being alone, particularly in urban settings and as the first lockdown stretched out like an old elastic band and the concept of time itself seemed increasingly pliable, I couldn’t help wondering whether this precipitous adoption of remote communication technologies was an entirely wholesome phenomenon.

The idea that the inexorable reliance on computers or artificial intelligence might not be all good is not a novel one. Academics and authors such as Sherry Turkle have challenged the propagation of this computerised utopia for many years, and these questions have also provided endless hours of cinematic material in movies such as The Matrix and I, Robot.

And while I’m certainly not trying to slap you across the face with the notion that communication technologies will singlehandedly herald the demise of humanity, I would raise a tentative hand to ask you to pause for a moment and consider how these technologies have impacted on your own relationships and your sense of connection to others.

Any commuter on public transport will be familiar with the experience of being surrounded by people, all mesmerised by their individual devices, oblivious to those around them (Or maybe you aren’t, which possibly also proves the point!). If you live in the average town or city you no doubt spend significant parts of every day slaloming around urban zombies who shuffle around heads bowed, entranced by their phones. Maybe these people feel hyperconnected, and thus unable to tolerate even a momentary detachment from their device in order to let the world and their immediate surroundings in via their other senses. They might even argue that they’re actually optimising their presence, making use of every possible moment to connect with someone or something and that the fact that this may seem to exclude people in their immediate vicinity is simply a quirk of geography.

This is the story the technology companies would have us believe, that our lives have been immeasurably improved by the ever closer integration of their software with our daily rhythms. That our addiction to their products is a surrogate for our innate desire to be closer to those who are meaningful to us. Viewed this way it’s impossible to be critical, because who would rebuke someone who just wants to be more connected to their friends and family, right?

But perhaps the counterargument rests on an appraisal of the gap between the quality of the connections we crave and those we manage to achieve via these communication technologies. In her book Alone Together Turkle argues that one of the dangers of increasing remote communication is a progressive sense of disconnection that makes achieving sincere or meaningful communication much more difficult:

"Texting an apology is really impersonal. You can't hear their voice. They could be sarcastic, and you wouldn't know.”…”It's harder to say ‘Sorry' than text it, and if you’re the one receiving the apology, you know it's hard for the person to say 'Sorry.' But that is what helps you forgive the person - that they're saying it in person, that they actually have the guts to actually want to apologize." In essence, both young women are saying that forgiveness follows from the experience of empathy. You see someone is unhappy for having hurt you. You feel sure that you are standing together with them. When we live a large part of our personal lives online, these complex empathetic transactions become more elusive. We get used to getting less.

Alone Together, 3rd edition, p. 234

If we are ‘getting less’ meaningful connection with others as a consequence of the shift to online communication methods, what can we do about it? Is it even a problem, or simply a function of progress in the same way that we came to rely less on horses to get to the shops after the introduction of the motor car?

My instinct tells me that this shift increases the risk of loneliness, even as the means of being connected to others proliferate. A range of people who depend on more than just instincts to make their pronouncements would also agree (phew). My ongoing ruminations about this idea - how our changed relationship to technologies due to COVID-19 has affected our ability to connect with each other - will form the next unit of my Reaching Out Into The Dark project and I’ll no doubt keep you updated in future posts.

I’d be keen to hear your views on this…what are your own experiences over the last couple of years? Does any of this ring true to you? Or do you feel that communication technologies and devices are inherently neutral and thus cannot be held responsible for anything other than the performance of the function for which they were designed? (Also a valid point of view)

Two other bits of news…

I’ve now set up a mailing list for those discerning people who want to be kept informed about what I’m up to. Thanks so much to those of you who suggested the idea and encouraged me to start one and to those who’ve already signed up. I am grateful for the support and to have you on board and I truly value the interactions and feedback these posts generate. The responses and counterarguments really help me further develop my ideas and I’m thankful for the stimulus to keep wondering. If you’ve not yet signed up but would like to, you can do so on this page.

The image below has been selected by Shutter Hub Editions for publication in their forthcoming collection ROAD TRIP, that explores the question ‘what does ROAD TRIP mean to you?’. The book should be available later this year and here’s hoping there’s at least one picture in it of a child screaming “are we there yet?” from the back seat.

And so we arrive at the end of another update. The only thing left to do is to close with a song (hehe, no I didn’t forget!)

Till next time…